Let’s talk about representations of gender, race and ableism in Joker and how to situate a critical reading in the local Australian context. I saw the film last night in Newtown, Sydney, where the mostly White audience erupted in rapturous clapping. We’ll explore this reaction.

Spoilers ahead. (N.B.: Read this as a gif-free version in PDF)

‘Joker’ presents a racialised and gendered view of class. Thomas Wayne (Gotham’s White male, super rich aspiring Mayor, played by Brett Cullen) is the antagonist. Wayne refers to protesters with contempt (jokers) and he punches Arthur (before his reincarnation as The Joker, played by Joaquin Phoenix) while he’s emotionally vulnerable. Whiteness prevails in this exchange, because the conflict between the two men is not really about class, as the film attempts to position. Their tension is about masculine power.

‘Joker’ presents a racialised and gendered view of class. Thomas Wayne (Gotham’s White male, super rich aspiring Mayor, played by Brett Cullen) is the antagonist. Wayne refers to protesters with contempt (jokers) and he punches Arthur (before his reincarnation as The Joker, played by Joaquin Phoenix) while he’s emotionally vulnerable. Whiteness prevails in this exchange, because the conflict between the two men is not really about class, as the film attempts to position. Their tension is about masculine power.

Masculinity

The Joker’s rise as anti-hero is celebrated as revolutionary in the film. It isn’t. Lower class White men view equity movements as encroaching on their social status. Joker simply re-legitimises White male anger as a political tool, which it always has been.

Arthur kills White affluent dudebros, an obnoxious White male talk show host (Murray Franklin, played by Robert De Niro), and a mean White male colleague. This inspires a revolution in Gotham, where men in clown masks riot. The film pitches this as social commentary, when in fact, it’s just White male ‘aggrieved entitlement.’

How does this translate to Australia? In Newtown, a gentrified suburb on Gadigal land, young White men around us physically jumped in glee, some acting out the punches on screen. Visceral responses to films are fine! But why might Joker feel like liberation to these young men? For one reason only: hegemonic masculinity.

Hegemonic masculinity reflects how some representations of masculinity win out over other expressions of manhood. The film industry (and other cultural institutions, like sport) assert narrow ideas of what it means to be ‘a man.’ The state uses overt forms of violence to establish and maintain power, but social institutions also use ideas to gain the public’s consent about the status quo. Hegemonic masculinity works by reproducing images, narratives and other symbols of masculinity to keep authority with dominant groups, especially White men. Joker dresses up Arthur’s escalating violence as emancipation. White men are invited to feel elation because the ‘under dog’ (Arthur) claims his rightful place at the top.

Environmentalism is one example of counter-hegemonic masculinity. The movement preaches (though does not easily achieve) gender equality. Two weeks after the historic climate change march (held on 20 September), where a record 300,000 Australians joined students in protest, there is still an audience keen to cheer Arthur’s destruction and misogyny.

Environmentalism is one example of counter-hegemonic masculinity. The movement preaches (though does not easily achieve) gender equality. Two weeks after the historic climate change march (held on 20 September), where a record 300,000 Australians joined students in protest, there is still an audience keen to cheer Arthur’s destruction and misogyny.

Can you be an environmentalist and still enjoy Joker? Yes! But as bell hooks tells us, we can savour films but remain critical. Let’s continue our exploration.

Gender violence

Arthur fixates on Sophie (Zazie Beetz). This is positioned as romance; a cinematic device to ‘humanise’ Arthur’s character. Their interactions are examples of gender violence, but they are not presented this way. In the words of the film, perversely spoken by Sophie, Arthur ‘follows’ Sophie for an entire day, through public transport, as she carries out her routine tasks and as picks up her child from school. This behaviour is actually stalking. Instead, Sophie is coquettish when she shows up unannounced at Arthur’s door that evening, and asks, ‘Were you following me today? (Smiling) I thought that was you,’ she says, when Arthur confirms.

Arthur fixates on Sophie (Zazie Beetz). This is positioned as romance; a cinematic device to ‘humanise’ Arthur’s character. Their interactions are examples of gender violence, but they are not presented this way. In the words of the film, perversely spoken by Sophie, Arthur ‘follows’ Sophie for an entire day, through public transport, as she carries out her routine tasks and as picks up her child from school. This behaviour is actually stalking. Instead, Sophie is coquettish when she shows up unannounced at Arthur’s door that evening, and asks, ‘Were you following me today? (Smiling) I thought that was you,’ she says, when Arthur confirms.

Sophie is a single mum, but she’s seen making herself available to Arthur for sex (after he’s made his first kill). She takes care of his emotions for the rest of the film, sitting all night long in the hospital with him, attending his stand up shows, and praising newspaper articles about the murders he’s committed (which she does not know are his doing). The interactions play on the audience’s perceptions, but the film ultimately excuses Arthur’s fantasies about Sophie as a symptom of his mental illness. As with other media portrayals of gender violence, including journalistic accounts of stalking, harassment and murder, the audience is invited to feel sympathy for the ‘socially awkward’ White man, and ignore that he has terrorised a Black woman.

Moving to another example of gender violence, Arthur kills his mother, Penny (Frances Conroy) after finding out that:

Moving to another example of gender violence, Arthur kills his mother, Penny (Frances Conroy) after finding out that:

- Due to mental illness, she believed Thomas Wayne was his father;

- Arthur was actually adopted; and

- Penny was a victim of intimate partner violence and ‘allowed’ Arthur to be physically abused by the same man.

Misogyny rules here. Joker relies on a dangerous misogynist trope; that women ‘lie’ about pregnancy for financial gain. Actually, misattributed parentage occurs in 1% of cases, mostly due to complex relationships, not money.

Still, Penny deserves to die by this logic. Arthur is justified to murder Penny after learning she is not his biological mother (a warped view on adoption and motherhood). The audience feels unencumbered because Penny was recast as a ‘bad’ mother (the worst thing a woman can be), and therefore Penny clearly didn’t deserve to raise her child in the first place. Penny is blamed for Arthur’s condition. Women who get locked up usually lose custody of their children (especially Aboriginal women imprisoned), and society is encouraged to think this is best. It isn’t. It merely plunges those women and their families into further poverty and ensures another generation will cycle through the criminal justice system.

Women like Penny are institutionalised for petty crimes, in connection to mental illness or substance abuse, overwhelmingly in the aftermath of domestic and family violence. Penny is seemingly sent to a criminal asylum due to her mental illness and for not intervening in child neglect – despite the fact that she did not have means to do so. Victims like Penny, women who cannot find safety for themselves and their children, are society’s throwaways, not the Arthurs of this world, who choose violence. Yet there is misplaced societal empathy for violent men keeping access to their children, even though it’s often a form of controlling their partners. Comparable concern is absent for mothers who survive gender violence. In fact, one in 20 Australians believe violence against women is sometimes justifiable. It’s no wonder that Arthur and the audience smugly shrug off Penny’s murder.

Let’s put all this back into local context:

- 44 women have been killed in Australia in 2019;

- 5 women were killed recently in a five-day period; and

- Nationally, one-third of women experience emotional abuse by a partner and one in four women have experienced at least one form of intimate partner violence.

Given the prevalence of gender violence, how is Joker an ‘anti-hero’ for us?

Race

Joker presents Arthur as an ‘every man’ whose poverty demands justice. It demotes Black women to stereotypes. Above all, Joker inverts gender and race dynamics in its attempt at ‘social commentary.’ In reality, Black women in the USA and Aboriginal women in Australia are central to civil movements. But this is not the world that Joker wishes to reflect. Joker re-imagines the world, so that a White man can lead a social revolution, when it’s actually Black women who’ve been at the forefront of social movements before, during and after the 1970s context of the film

Joker presents Arthur as an ‘every man’ whose poverty demands justice. It demotes Black women to stereotypes. Above all, Joker inverts gender and race dynamics in its attempt at ‘social commentary.’ In reality, Black women in the USA and Aboriginal women in Australia are central to civil movements. But this is not the world that Joker wishes to reflect. Joker re-imagines the world, so that a White man can lead a social revolution, when it’s actually Black women who’ve been at the forefront of social movements before, during and after the 1970s context of the film

In Joker, Black women are passive and unlikeable subjects so that Arthur can rise to prominence. Then there’s the fact that the film evokes New York – which is 27.5% Latin, 25% Black, 12% Asian, among Others – but a White man is elevated to protest warrior.

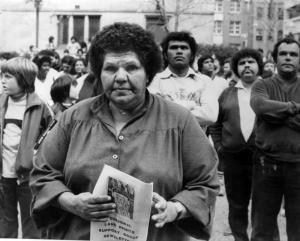

Joker contrives White heroism, so that non-Indigenous people in Newtown clap in a theatre, while oblivious of Aboriginal women heroes who have lived and worked in the area, like Dulcie Flower, Coleen Shirley Perry Smith (pictured), and Ruby Langford Ginibi.

Class

Arthur rages against ‘the system’ which has cut off funding to his mental healthcare in fictional Gotham. Yesterday, as we watched this film in Australia, poor and disabled people were subjected to renewed calls to shrink our public healthcare, via tax breaks to employers. In response to the climate march, the federal Government is now threatening to cut social welfare to people who protest. The Government continues to push ‘fatally flawed’ drug testing for welfare recipients, as a means to further demonise the most disadvantaged in society. Aboriginal communities in remote regions have been ravaged by the cashless welfare card, a system that denies them cash payments and forces them to shop at a limited number of over-priced stores. Yet the Government wants to expand the system, even though it ‘fails the human rights test.’

Arthur rages against ‘the system’ which has cut off funding to his mental healthcare in fictional Gotham. Yesterday, as we watched this film in Australia, poor and disabled people were subjected to renewed calls to shrink our public healthcare, via tax breaks to employers. In response to the climate march, the federal Government is now threatening to cut social welfare to people who protest. The Government continues to push ‘fatally flawed’ drug testing for welfare recipients, as a means to further demonise the most disadvantaged in society. Aboriginal communities in remote regions have been ravaged by the cashless welfare card, a system that denies them cash payments and forces them to shop at a limited number of over-priced stores. Yet the Government wants to expand the system, even though it ‘fails the human rights test.’

Who needs 1970s Gotham when this is modern-day Australia?

Ableism

Joker relies heavily on ableism. Arthur suffers from uncontrollable laughter (pseudobulbar affect, which also refers to spontaneous crying). Colleagues and strangers make fun of him. But this is just a set-up to excuse his violence, reproducing the stereotype that mental illness equals violence.

Joker relies heavily on ableism. Arthur suffers from uncontrollable laughter (pseudobulbar affect, which also refers to spontaneous crying). Colleagues and strangers make fun of him. But this is just a set-up to excuse his violence, reproducing the stereotype that mental illness equals violence.

Then there’s sexist ableism: Penny, who is a White woman, is mentally ill, as well as physically disabled. She’s snuffed out to unburden Arthur as his carer. The act pushes his re-birth as The Joker. Audiences cheer Arthur’s metamorphosis, as he transcends his disability, a plot point used to selectively excuse violent White men in countless films, endless media coverage of gender violence, and racist attacks.

Back to the cheering Newtown audience: our nation’s apathy for disabled people is epic, especially Aboriginal people who suffer most due to under-resourcing and institutional violence. Would we clap for these Others? Of course not. Disability is a prop to celebrate White men’s hedonism.

Back to the cheering Newtown audience: our nation’s apathy for disabled people is epic, especially Aboriginal people who suffer most due to under-resourcing and institutional violence. Would we clap for these Others? Of course not. Disability is a prop to celebrate White men’s hedonism.

Joaquin Phoenix’s performance is as commanding as everyone has been raving, yet his portrayal is not without issues. Phoenix is very talented. He could have rendered a profound performance if Arthur had simply been an angry, isolated man. But he was portrayed as disabled to give the filmmaker license on his violence, banking on accolade given to able-bodied actors who manipulate disability to gain sympathy.

‘Social commentary’ for White men

Joker director, Todd Phillips, claims he was driven from making comedies due to ‘woke culture.’ The origins of this term is an appropriation of Black activism, and subsequent backlash, especially by White men who feel ‘aggrieved entitlement’ to be sexist, racist, ableist, transphobic and homophobic.

In light of Phillips’ comments, Joker’s pretence to class liberation is exposed as the same brand of nihilism fueling incel (involuntary celibate) ideology. Which is to say, this film is really just old-fashioned patriarchy rehashed as ‘resistance.’

When Joker begins, we see protesters holding ‘RESIST’ signs – an allusion to anti-Trump protests in 2017. However the film ends with The Joker’s sycophants holding RESIST signs upside down. White patriarchy’s co-opting of social protest, centring White violence, wins in the end

When Joker begins, we see protesters holding ‘RESIST’ signs – an allusion to anti-Trump protests in 2017. However the film ends with The Joker’s sycophants holding RESIST signs upside down. White patriarchy’s co-opting of social protest, centring White violence, wins in the end

Joker is entertaining. I’ve unpacked dynamics showing why the film is far from transformative cinema, as some White critics claim. For example, see comparisons to ‘Get Out,’ showing how White people are eager to assimilate Black excellence, especially in a film that undervalues Black women.

Enjoy the film – I did, to a point – but don’t mistake it as social commentary. It speaks only to White men who think the world owes them free reign; it invites able-bodied people to cheer for caricatures of disability; and it dresses up patriarchy as liberation.

From beginning to end, Joker does nothing new.

Thank you so much for this. You are so insightful… although I’d thought already about the disability and mental illness in the film (which I also saw in Newtown, with a laughing but largely woman audience) I hadn’t processed race or gender. It’s interesting that the Extinction Rebellion takeovers begin today… I wonder how many of the young white men leading that movement will see this film and identify?

LikeLike

Hi Meredith,

Thanks very much for your comment. Your question is a good one! It’s interesting because the origins of the Extinction Rebellion started as an academic protest, drawing inspiration on feminist and civil rights movements. So in principle, it should be inclusive. But it quickly became a White space, including racist dog whilstling from within the movement’s media arm. The same was the case with Science March, where racism, ableism and sexism made the protests unwelcoming to minorities. There’s a sub-cohort of young White men who see climate activism as their domain to re-assert their dominace (‘eco-fascism’). Would the White men participating in Extinction Rebellion identify with the ‘Joker’? It’s unlikely for most of them, because the movement predates the film. However, the White men currently harassing me online because of my post on ‘Joker’ (‘you’re stupid, this film is not for you!’) use similar language to eco-fascists. Whether it’s a film or environmentalism, these angry White men demand that we go along with their narrow and uncritical idea of the world, or be subjected to more vitriol.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Dear Zuleyka Zevallos, although I havent seen the movie (because I cant watch films with violence) I strated reading your article with growing interest as I am a white disabled feminist trying to learn more about privilege, ablism and power. Unfortunately it was impossible for me to read your text due to the constant movements caused by the animated images. As it it already hard for me to read, it is even harder with movement occuring at the same time due to my disablilty. It would be lovely if you could keep that in mind for futher writings. I am sure your text wouldnt loose anything by using no gifs and less images all together. On the contrary.

Greetings from aound the globe,

Johanna

LikeLike

Hi Johanna

Thanks for your comment. You can read a gif-free version here: https://othersociologist.files.wordpress.com/2019/12/the-other-sociologist-gender-race-and-ableism-in-joker.pdf

LikeLike

Thank you!

LikeLike

Hey, fellow sociologist here. I’ll talk from my point of view (as an afro-latino cis man) I really liked Joker when I saw it, but I still thought about criticicisms like the ones you have. I also found the treatment of race and gender issues underwhelming, but I gave the masculinity portrayal a different reading: I felt a Fight Club vibe. Just like Tyler, Arthur is a frail, egotistical representation of underdog masculinity trying to emerge. Both eventually “succeed” (in their own macho terms) after blaming others for their misfortunes, but I don’t feel that we as an audience are supposed to applaud that. However, your analysis helped me understand why i felt unsatisfied: superficial treatment of those subjects implied (or revealed?) the simplistic and posibily misoginystic views of the authors.

Glad I found this site!

LikeLike

Hi Ale,

Thanks for sharing your thoughts. This is a good comparison you raise, as Fight Club is a also a movie that engages with a cis-White male ‘crisis’ of hegemonic masculinity.

LikeLiked by 1 person