By Zuleyka Zevallos

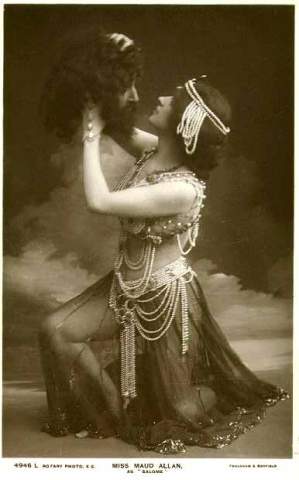

This story is engrossing: Maud Allan was a Canada-born dancer who found fame in Germany in the early 1900s. She performed in the Oscar Wilde play, Vision of Salome, famous for “the dance of the seven veils.” When Allan was in her 20s, her brother was executed for killing two girls. She changed her name to escape this notoriety but later found herself the subject of infamy, drawn into a litigation case defending her name against charges of “sexual perversion.” Allan’s artistic sensuality and the fact that she was a lesbian were weaved into a conspiracy plot involving the highest office of British parliament. The Daily Mail recently reported on Allan’s life as a new play is being produced in San Francisco which is based on this salacious court case.

This story is engrossing: Maud Allan was a Canada-born dancer who found fame in Germany in the early 1900s. She performed in the Oscar Wilde play, Vision of Salome, famous for “the dance of the seven veils.” When Allan was in her 20s, her brother was executed for killing two girls. She changed her name to escape this notoriety but later found herself the subject of infamy, drawn into a litigation case defending her name against charges of “sexual perversion.” Allan’s artistic sensuality and the fact that she was a lesbian were weaved into a conspiracy plot involving the highest office of British parliament. The Daily Mail recently reported on Allan’s life as a new play is being produced in San Francisco which is based on this salacious court case.

Allan’s story makes an excellent historical case study of the criminalisation of femininity and homosexuality in Britain at the end of World War I. I discuss the contradictory meanings of Allan’s dancing and her embodiment of the character Salome, a figure that has come to represent the dangerous qualities of female heterosexuality. The cultural significance of Allan’s dancing and her court case takes on multiple meanings in light of Allan’s reality as a lesbian woman in the 1920s.

I use Allan’s story to examine the history of the clitoris and its cultural mystique in relation to cis-women’s* bodily experiences of pleasure in connection to dancing and sex.

Knowledge of the clitoris as proof of sexual deviance

Born in Canada and raised in the USA, Allan moved to England in 1916 to bolster her career in stage and film. British Minister Noel Pemberton Billing was extremely hostile of Allan, as she was rumoured to be the lover of a former British Prime Minister’s wife. According to the Daily Mail, Billing was a right-wing conspiracy theorist who believed there was a “secret homosexual agenda” behind Germany’s political action in World War I.

The LGBTQ Encyclopaedia reports that Billing believed there were close to half a million Germans who could contribute to a “black book” filled with British state secrets, garnered through “sexual peculiarities.” Billing publicly proclaimed Allan to be a spy, writing a document which was absurdly titled “The Cult of the Clitoris.” Billing alluded to Allan’s homosexuality as proof of her sexual vice.

Her brother’s crimes were later raised as further evidence that her sexuality may be genetically predisposed towards criminal and immoral behaviour. Allan sued Billing for defamation – and lost, but the case caused an uproar in 1918.

During the trial, Billing’s collaborator explained that the use of the word “clitoris” in the document that accused Billing of being a sexual deviant and spy was a deliberate ruse to weed out sexual transgressors. The term was provided by a “village doctor.” The word “clitoris” was then an esoteric term that they claimed “would only be understood by those whom it should be understood by… [as it describes an] organ that, when unduly excited… possessed the most dreadful influence on any woman…”

The fact that Allan knew its meaning, coupled with her famous dance in the play Salome, supposedly stood as proof of her sexual deviance. Other than the political hyperbole linking homosexuality to political espionage (a study for another time!), there are two facets of Allan’s supposed “deviance” that I will focus on: knowledge of the clitoris; and the relationship between femininity, dance and arousal. The link between these two phenomena is the danger that women’s active sexual knowledge poses to heterosexual social order.

Historical understanding of the clitoris

Knowledge of the clitoris may have been deemed the scientific measure of a deviant woman in the 1920s, but it remains cloaked in some measure of cultural mystery even today. The power of the clitoris is that it has the potential to disrupt how Western (and other) societies think about and organise sexuality. Heteronormativity describes the taken-for-granted and institutionalised ways in which a patriarchal vision of heterosexuality dictates the “natural” order of society. Society judges all expression of sexuality against heterosexual ideals and silences homosexuality and other forms of sexuality (including asexuality).

Heteronormativity positions vaginal intercourse between a man and a woman* as the primary definition of “sex.” In this view, biology supposedly governs sexuality, but it is actually culture, rather than some innate imperative, which mediates sexuality. The historical understandings of the clitoris and its cultural significance have changed surprisingly little over time. Today, national surveys continue to find that vaginal intercourse is the primary sexual activity for heterosexual people, even though it means that at least one third of women do not reach orgasm. This is in comparison to only 6% of men who do not reach orgasm during sex. (For the Australian data, see Doing it Down Under.)

Studies consistently show that women’s inability to orgasm is not generally due to some physiological or psychological problem. As researchers Juliet Richters and Chris Rissel point out, clitoral stimulation (and oral sex) are the main ways that women achieve orgasm, but a significant group of men do not focus on the clitoris when they have sex with women, and some women do not change this focus.

Women’s bodies, in various states of undress, are pervasive in mainstream popular culture in many societies, especially in Western and technologically advanced nations. The way in which women’s bodies work, however, is still a terrain of myth and invisibility. Elite, well-educated women who know the correct terms for their anatomy still refer to their vaginas as “down there” or as their “private parts,” whether they live in Hong Kong or the United States. In the 1970s Germaine Greer tried to reclaim the word “cunt” to change its meaning from negative curse to a symbol of women’s sexual power. As she tells it, she failed. Pussy Riot and other female artists are similarly engaged with changing the discursive practices that stop women from using the word “pussy“. In general, providing women with the opportunity to talk about their vaginas, let alone their clitoris, in a safe, public way signifies a tremendous cultural effort.

Dennis Waskul and colleagues have used the concept of “symbolic clitoridectomy” to examine how the cultural taboos around talking about the clitoris directly impact on heterosexual women being able to know their bodies. The researchers quote author Suzie Bright, who demonstrates how the cultural ignorance about the clitoris is ludicrous given that men do not experience the same discursive problems in naming and understanding their sexual bodies:

I never met a man who told me he didn’t know how to come or didn’t know where his penis was. That pretty much sums up the dilemma of women’s sexual responsiveness. Lots of women have never even said the word “clitoris” or touched their clit, and don’t really have a good idea about their genitals at all.—Suzie Bright, The Sexual State of the Union (1997).

Given that the clitoris is rarely discussed or given equal footing in cultural discourses of heterosexuality in the present day, we can see how Allan’s professed knowledge of the clitoris was scandalous over one century a go. Being self-possessed about her body and her sexual pleasure was a disruption to the the way in which femininity and heterosexuality was (and still is) socially constructed.

Dance as the embodiment of feminine self-pleasure

Allan’s artistic expression riled Billing not simply because she was a homosexual woman, but because she represented a new form of femininity that had not yet been witnessed in British dance. Leading up to the 1920s, women dancers were still expected to convey demure nobility. Allan presented a new style of artistic embodiment (bodily presentation) to which upper class audiences were unaccustomed. She wore relatively little clothing on stage, and her movements signalled a new “non-verbal… vocabulary” that contested acceptable femininity and sexuality, as Judith Walkowitz argues:

When the North American dancer Maud Allan introduced the “new,” “expressive” dancing into London in 1908, her “nude exhibition” before an audience of “richly clad” Londoners and foreign visitors incited fantasies of escape and pleasure, while simultaneously provoking anxieties of dislocation and unease… Let me summarize the striking features of the body idiom performed across Allan’s repertoire: a solitary, autonomous, unfettered, mobile, weighted, and scantily clad female body whose movements delineated emotional interiority, shifting states of consciousness, and autoeroticism. To be sure, Allan’s gestural system built on available constructions of corporeality and subjectivity, but it gave unusual status to a self-pleasuring, embodied, and expressive female self and to the staging of the internal process of consciousness in public. [My emphasis.]

Perhaps it wasn’t simply that Allan portrayed a sexualised vision of femininity, but rather that her dance movements were focused on her own pleasure that posed a threat to British society (according to Billing). Dancing that involves disrobing presents a complicated site of feminist protest. Radical feminists reject the idea that a woman using her body to gain any level of power over a male audience is in any way positive. Instead, it is seen to be counter-productive to social transformation.

Other writers argue differently. Journalist Toni Bentley looks to the history of Salome and other forms of “naked dancing” as an exercise of power and as a challenge to restrictive social mores. (See also sociologist Danielle Egan who makes a similar argument about the negotiation of power between exotic dancers and their clients.)

It is, of course, problematic to simply read Allan’s dancing as a feminist stance. Allan did not align herself with the women’s rights movement that had already broken out (the suffregettes); she did not stand up on stage and scream out for equal rights; nor did she publicly identify as a homosexual woman. How might we unpack the contradictory meaning of Allan’s dancing as sexual protest?

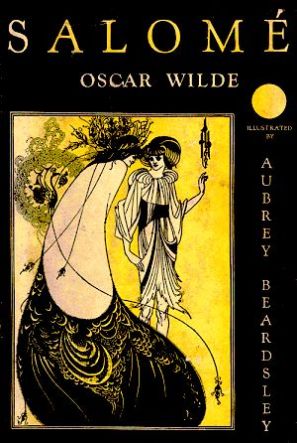

Salome and the “dance of the seven veils” in critical context

Allan’s “dance of the seven veils” is a vexing case of feminist protest when its historical context is deconstructed. The play Salome has its origins in the biblical story of John the Baptist. In the Gospels of Mark and Matthew, Salome is not named. Instead, she is referenced as the daughter of King Herod,** who was so “pleased” with the way she danced that he promised her anything she desired. Salome and her mother are understood to have colluded to ask Herod for John the Baptist’s head. Herod is depicted as being saddened about fulfilling this request, but he’d given his oath and so he orders the execution.

Salome’s beauty and enchanting dance represents the danger of female sexuality: women’s body movements incite weakness and lust in men (including their fathers, in this case). The female body in motion can force even the most powerful leaders to give in to evil deeds. This story represents the “madonna-whore” dichotomous view of women in conservative interpretations of the bible. Fundamentalist Christian traditions see women only as saints (epitomised by the Virgin Mary) or as sinners who need to be saved (Mary Magdalene), and temptresses who use sex to overpower men (Jezebel, Judith, Delilah to name a few). Then again, the original text does not describe Salome’s dance style. Early translations of these passages suggest that it was Salome’s mother who asked for John’s head, not Herod’s daughter.

Nevertheless, the character of Salome continues to represent the folly of female sexuality in other artistic incarnations, including in various paintings (see above), Wilde’s play, and the opera based on Wilde’s work. Feminist cultural critic Janet Wolff notes that there is little stage directions in Wilde’s play about how the dance should be enacted (see p.70-72). Wilde is said to have wanted the character to convey a conscious, “infinite” lust, and a “perversity without limits”, while at the same time being chaste, like a shrinking flower: “Her body, tall and pale, undulates like a lily… The richest lilacs cover her svelte flesh” (p. 3).

The the overt sensuality that Allan and various other performers imbue into this dance reflects a vision of Orientalism. As Edward Said explains, Orientalism takes a reductionist view of “Arab”, “Middle Eastern” or “Islamic” people, collectively portraying them as a singular group of exotic, uncivilised and dangerous Others. The Muslim woman’s veil covers a body that promises to shed its layers of chastity to reveal unbridled sexual debauchery.

The photos above show Allan costumed in a beaded bra and belt, her stomach exposed and her legs covered by a sheer material. Allan’s dance portrayal of Salome, referred to colloquially as the “dance of the seven veils”, is a colonial fantasy of Islamic “harems”. Western cultures similarly imagine the sexual otherness of “veiled women” in a restrictive dichotomy set against the harem, “where women were distanced from everything that had any semblance of power”, as Fatima Mernissi details in Islam and Democracy. Today, the Muslim veil and dress (hijab), are generally read as representing Muslim women’s oppression; their dress hides them away from the eyes of the world. In this (mis)reading of Islamic femininity, Muslim women are passive, dehumanised and sexless.

At the peak of colonialism, the veil represented the mystique of Muslim women as exotic creatures. The dance of the seven veils positions Islamic femininity as burlesque, as a titillating promise of layers of clothing being shed for the visual pleasure of men. Neither view of femininity does justice to the diverse experiences of Muslim women, and in fact, both views place women in a subordinate position, as the chattel of men.

The character of Salome and the dance of the seven veils are both used to depict a sexist view of female sexuality. Dancing women represent sex – a particular type of heterosexuality, to be exact; in which women’s bodies, their sensuality and their movements are for the exclusive enjoyment of heterosexual men. As a white woman from a Western culture, Maud Allan reproduced a colonialist fetish of Islamic women as the savage Other. As a white, Western lesbian woman, Allan’s performance carries additional contradictory meaning.

Society overtly demanded that women’s sexuality be focused on men’s desires, rather than on their own sexual fulfilment and certainly not towards other women. Coupled with her private life as a homosexual woman, Allan represented a challenge to patriarchal norms about women’s heterosexuality. Rather than appearing as a passive flower who swayed lightly to a gentle rhythm, Allan was a self-assured woman whose dancing conveyed that she understood her body. She knew what the clitoris was, and when asked in court, she acknowledged its meaning as a focal point of women’s bodily pleasure.*

Her crime was conveying an active femininity and sexual gratification that not only put men in the role of passive spectator.

A contradictory challenge to heteronormativity

Heteronormativity makes non-heterosexual identities, desires and practices invisible or deviant. Homosexuality, although increasingly acceptable in various societies, is still positioned as a minority experience in most social hierarchies. Homosexual people do not have the same rights as heterosexuals and the expression of same-sex desire is largely relegated to the private sphere. That is, societies have set up boundaries as to when, where and how it is appropriate for non-heterosexual sex to be represented.

Heteronormativity dictates that lesbians are only allowed to be seen as sexual beings when they embody a particular type of beauty, playing out particular types of sexual acts that align with the heterosexual male conception of “lesbian sex.” A lesbian who enjoys their sexuality in an active manner, outside of this script, is not constructed as desirable, but rather she is positioned as a danger to heterosexual power relations.

Allan was deemed a danger to British society because she was overtly sexual, confident and unwilling to slink into the shadows of polite society. She stood up for her character, relying on the law to acknowledge her rights against slander. The law failed her but Allan’s story resonates today as women’s femininity and heterosexual non-conformity continue to be policed.

Women’s sexuality is restricted in tacit ways in everyday life, such as by the fact that many women struggle to talk about their clitoris and negotiate their sexual pleasure. Heteronormativity controls sexuality in more formal ways, such as through restrictive reproduction laws and through the denial of marriage rights to lesbian, gay, transgender, queer and intersex communities.

Allan’s court case brings no neat narrative about the connection between dance and women’s embodied sexualities. The contradictions that her story represents are worth thinking through in historical context. There are threads weaved within her legal plight that resonate with the present day. For example, the appropriation of fetishised otherness, the social construction of sexual deviance and the politics of women’s bodies.

How far has Western culture come since the 1920s in its treatment of women’s bodies and their sexuality? I want to take these themes up again in the near future, by delving further into the social construction of heterosexual desire and its connection to Otherness

Connect With Me

Follow me @OtherSociology or click below!

Notes

*A “cis woman” is a person whose biological body and gender identity match. This term acknowledges that intersex, transgender and other expressions of femininity do not always match the biological traits usually attributed to a “woman.”

**Scholars dispute that Herod’s daughter was named Salome. See Women in Scripture, p. 95.

Read more

On the social hierarchy of sexuality, read Gayle Rubin’s classic essay “Thinking Sex: Notes for a Radical Theory of the Politics of Sexuality.”

For a great discussion on “the harem” as the focal point from which Western cultural fantasies about Muslim women developed and the politics of the veil, read Fadwa El Guindi’s Veil: Modesty, Privacy and Resistance.

Credits

Daily Mail link via Lucia Thamar Valente Cavalcante.

3 thoughts on “The “Cult of the Clitoris”: Policing Women’s Sexuality in England During WWI”

Comments are closed.