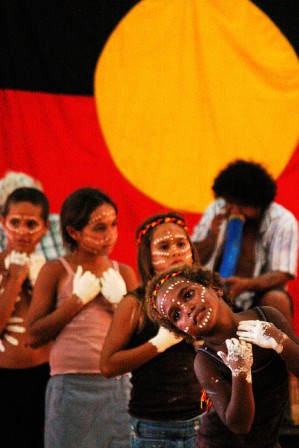

Today marks the 11th anniversary of former Prime Minister Kevin Rudd’s Apology to the Stolen Generations. From 1910 to 1970, up to one third of all Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children (100,000 children) were forcibly removed from their families and sent away from their communities. They were classified according to their skin colour and put into Christian missionaries where they suffered abuse and neglect, or they were placed with White foster families who did not understand their needs. These children were forced to forget their language, culture and spirituality, and in many cases they were not told of their Indigenous heritage.

The Bringing Them Home report of 1997 gathered evidence of the impact this cultural genocide had on Indigenous Australians, showing that it led to intergenerational trauma, poor health, and socio-economic issues. The report made 54 important recommendations to end the cycle of violence against Indigenous Australians.

Twenty years later, Indigenous children are being removed from their families up to four times the rate.

Join the Grandmothers Against Removals, protesting forced adoptions law in NSW. Their ethos is that: ‘The best care for kids is community.’ Below are my live-tweeted comments, beginning at the Archibald Fountain in Sydney.