My Weekends With A Sociologist series is going to start coming to you more frequently and completely out of sequence. I will share with you my visual sociology adventures from different places, at different points in time, showing you what has captivated my sociological imagination most recently, through to what has lingered with me over time. The purpose of this series is to showcase what it is to see the world through a sociological lens. (For visually impaired readers, descriptions in the alt.) So let’s get started!

What better way to restart our journey, than with the enduring legacy of a strong Aboriginal woman, Barangaroo.

Beginning in the first week of January, Sydney annually hosts the Sydney Festival, with various sites around town housing performances, public art and sculptures, including many interactive installations. The best this year was the artwork, Four Thousand Fish, curated by Emily McDaniel, artist from the Kalari Clan of the Wiradjuri nation in Central New South Wales. The artwork blends sea song, visual story telling, sound, lighting, sculptures, landscape photography, music and of course, a beautiful nawi (bark canoe).

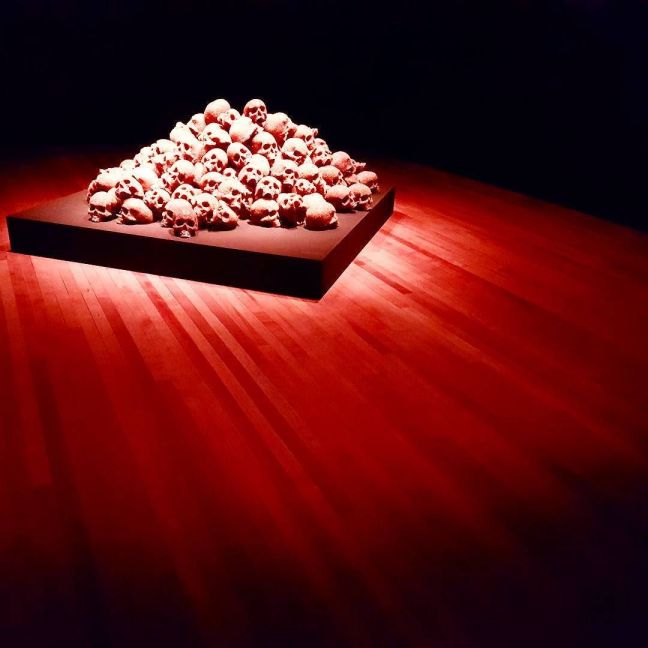

Held at the Cutaway in Barangaroo, every weekend this past January, the site was transformed into a public art sculpture that was set ablaze nightly at dusk. I attended an event hosted by the beloved street photographer, Legojacker (formerly from Melbourne, they had moved to Canberra in recent months).

Barangarro is named after the mighty Cammeraygal woman of the Eora nation, who defied colonialism in Gadigal, her homeland (also known as Sydney).