A new sociological study finds that unfollowing people on Twitter has little to do with frequency of interpersonal contact between two parties. Rather it has more to do with people who break specific social norms of Twitterverse etiquette. This got me thinking about the unique aspects of Twitter connections, as well as the ways in which unfollowing on Twitter might be similar to the way other social networks operate offline.

The International Data Group has blogged about a study by Professor Sue B. Moon from the Korea Advanced Institute of Science and Technology. Moon took daily snapshots of 1.2 million Korean-speaking Twitter users for 51 days and she also conducted 22 in-depth interviews to get a qualitative understanding of their behaviour. Moon’s study finds that 43 percent of active users ‘unfollow’ someone at least once in 51 days. The average person unfollows 15 to 16 people in that time period. According to the article, people are more likely to be unfollowed when the relationship is:

- one-way (such relationships are ‘fragile’ and they are two and a half times more likely to be unfollowed)

- new

- not informative

Moon’s interviews further showed that people who tweet too often and who consequently dominate a timeline are more likely to be unfollowed, as are people who tweet on uninteresting, mundane or political topics.

Conversely, users who are retweeted by others are less likely to be ‘unfollowed’, as are Twitter relationships that have overlapping ties. Most interestingly, lack of direct interaction is not correlated with unfollowing behaviour. Moon found that 85.6 percent of the Twitter relationships she studied do not involve any interpersonal exchanges (including replies, @mentions or retweets) and 96.3 percent of Twitter relationships survive on fewer than three exchanges.

Moon noted that traditional media and marketing campaigns do not understand these nuances of social media relationships and online etiquette. As such Moon argues large corporations have not been very successful in capitalising on the full potential of social media platforms.

Most studies on Twitter trace the patterns of information and social exchange between active relationships. Moon notes that her study is unique because it offers sociological data on the break-up of online social networks (rather than on existing links).

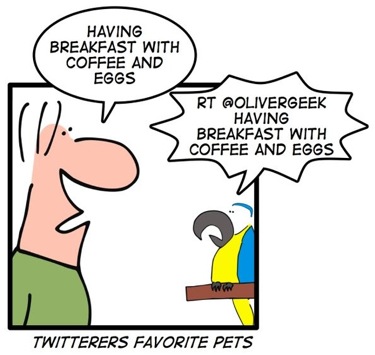

Moon’s research reiterates that online behaviour conforms to other offline social behaviour, as Barry Wellman and Caroline Haythornthwaite have been arguing about the net for yonks (as have others). Sociologists find that strong social networks are sustained by dense social ties, norms of reciprocity, trust and affinity. Length of time of the relationship also matters. It seems all of this is also true of Twitter networks, with retweets signifying trust and longevity of ties over time. (As I previously discussed, research finds that few Twitter users generate original comment, instead posting on other people’s content. Retweeting information is therefore a vote of endorsement of popular Twitter users.)

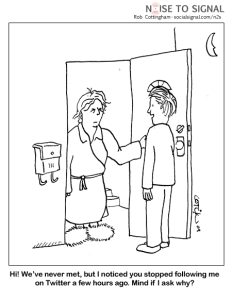

At the same time, although Twitter relationships operate through somewhat familiar conventions, some of its interpersonal communication features are unique. Moon mentions that unlike other face-to-face relationships, choosing to unfollow someone on Twitter does not require the notification or approval of the other party.

Moon’s findings on unfollowing may be culturally specific to Korean users. Then again, other sociological research published in Science and recounted in the New York Times suggests an intriguing premise that the moods of Twitter users follow similar trends across cultures. Scott Golder and Michael Macy studied the tweets of two million users across 84 countries. Their study was not measuring unfollowing trends, but their data show that there are emotional similarities in the daily and seasonal use of Twitter. (The researchers find that people tweet unhappy messages in the mornings, even on weekends.) Perhaps Golder and Macy are onto something. Other reports on influential Twitter users show that unfollowing people unleashes a massive emotional backlash from users.

There exists a tacit Twitter norm which compels some people to automatically follow back everyone who follows them. When someone has thousands of Twitter followers, however, this practice makes Twitter feeds hard to manage and it attracts spammers. This has led to a couple of infamous cases of Mass Unfollows. Mashable reported in 2009 that when Robert Scoble unfollowed 106,000 people, more than 7,000 accounts immediately unfollowed him back. Scoble assumed that they were either spambots or lameos who were only following him to get a higher follow count in the first place. Not cool dudes. Scoble noted his spam automatically ended when he unfollowed everyone, so there was instantaneous benefit for him in taking such drastic action.

Similarly, in early September, Chris Brogan noted that he had been receiving 200 daily spam messages because of his Twitter account, which had 131,000 followers. Brogan says that he had not able to use Twitter effectively because there were simply too many people on his feed. Consequently he announced he would be unfollowing everyone and that it was nothing personal. Despite this disclaimer, he was inundated by highly emotional responses from perfect strangers. Some people were hurt and upset; others said they had felt privileged to have been followed in the first place. Brogan called this his Great Twitter Unfollow Experiment. In his blog, he summarised that followers:

- tie ‘emotional worth to following’: people pleaded with Brogan not to unfollow them, telling him how upset and sorry they were that he stopped following them

- see following as an ‘endorsement’ of character: people publicly mused as to why he may have unfollowed them. For example one person tweeted: I haven’t read @chrisborgan’s tweets much lately. Maybe that’s why he unfollowed me. : (

- wanted to keep ‘the channel [of communication] open’ even after he unfollowed them.

- wanted reciprocity: people publicly tweeted that they were unfollowing him because he unfollowed them.

- assume the rules of Twitter are set: Brogan disagrees with this notion. He sees that the social norms of Twitter are ‘imaginary’ and they can therefore be tested and modified to suit an individual’s ‘own way’. He suggests the rules one follows on Twitter should ‘Make it valuable for you’.

For some people, Twitter unfollowing is emotionally fraught and presumed to be an act of denigration. For others, unfollowing is either a necessary action to make Twitter interaction with others more meaningful. Either way, sociology research highlights how social norms that underpin other social networks offline also apply online, but other social norms that are unique to Twitter are still being negotiated by users.